Grades: 5-8 (two 45-60 min lessons)

Many teachers are in the habit of creating a class contract outlining expectations of

derech eretz—how students should behave and treat one another. This activity is

designed to help build a class contract, a class “haskama” (community agreement), to

deal with interpersonal relationships and the classroom environment (as opposed to

expectations regarding homework, supplies, etc.)

Background:

Throughout history, Jewish communities created haskamot (agreements) to help guide

individuals as to how to behave towards one another. These agreements could only be

made when all members of the community were present and only if all, or at least

most, members of the community came to consensus on them.

Goals:

Students will know about the Jewish tradition of creating community haskamot. They

will consider the behaviors that build or destroy class community. Students will create

a class haskama based on their thinking.

Lesson Activities:

- Introduction: Community Web

- Text Study: Haskamot

- Create a Classroom Haskama

- Wrapping Up

Lesson Activities

Introduction: Community Web

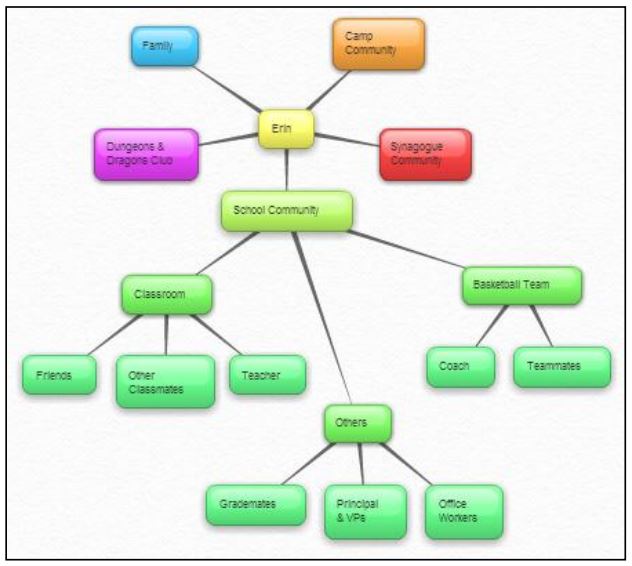

- Tell students that often we talk about belonging to a community. In reality, we

belong to multiple communities. In this activity, students are asked to create a web

of the various communities they belong to. Begin by modelling how you would

create a web of your communities. Put your name in the middle, and then branch

out to various communities such as school, family or synagogue. Then, add “subcommunities”.

“Class” might be a sub-community of school, for example, and “youth

committee” might be a sub-community of synagogue. An example of the beginning

of a student community web can be found in the diagram below.

Tell students that in general, every community has its own set of rules, formal and

informal. There are certain things that are acceptable to do with camp friends, for

example, that might be taboo with school friends. It is important to ensure that

everyone feels comfortable, safe and valued in this community of students and

teacher. Tell students that the goal of this lesson is to set the foundation for this safe

community.

Text Study: Haskamot

- Tell students that the Rabbis understood the idea that different communities

needed different rules. Whereas there is halachah that applies to all of the Jewish

community, the Rabbis also created another approach to deal with the particular

needs of community at a given time. This text tells about this approach.

- Read the text at the end of this lesson together. The text is taken from the “Pele

Yoetz”, a book of mussar (ethics) written in the early 19th century by R. Eliezer Papo

of Constantinople. In this text, students discover the concept of a haskama, a formal

agreement. It is particularly noteworthy how flexible the haskama is—it is

designed to meet the needs of the time. Ask students: Based on this text, what seems

to have been a “need of the time” in the time of R. Eliezer Papo? It seems that

“excessive spending” was an issue. Rules were created, for example, to limit the

amount of spending on a simcha. If there is time, discuss what impact this might

have on Bar and Bat Mitzvah celebrations if, for example, the maximum allowed to

be spent was $5,000.

Create a Classroom Haskama

What follows are two different options for creating a classroom haskama. Select the one

which you feel will be most successful in your classroom.

OPTION 1: COMMITTEE WORK

- Divide students into small groups (two to four students per group). Have each

group come up with no more than four key rules that they feel will cover what

members of the classroom community need to remember about how to act towards

one another. Obviously, one could come up with more than four rules, but by

limiting it, it focuses on what is most important. It also makes it more likely that the

students will be able to succeed. Instruct students to word their rules in the positive

– as opposed to what should not be done. You may wish to practice this with

examples of rules such as the following being careful not to give so many examples

that it takes away from the activity:

- Negative: No interrupting when someone is speaking

Positive: Only one person speaks at a time

- Negative: No putting up your hand when someone is talking

Positive: Put up your hand only when no one has the floor

- Negative: No put downs.

Positive: Always speak respectfully to one another.

- Next, do one of the following:

- Have the first group read out one of its rules, and write the rule on the board.

Ask if others had written a similar guideline on the same topic. If so, have them

read their versions out loud. If the other versions add something important, or

have better wording, make edits without straying too far from the original.

Repeat this process starting with the next group until all of the rules are on the

board. Next, as a class attempt to determine which four rules are the most

important and should be made into the class haskama. If there is a strong feeling

that five or six or only three rules are needed, then allow the class to make that

determination, so long as each guideline is unique. OR

- Have the group nominate one member to represent them. These volunteers will

serve on a committee and meet with the teacher at lunch, recess or study hall to

determine a proposal for a classroom haskama based on each group’s work. The

committee is then tasked with presenting the haskama to the class. The class is

then asked to ratify the document through a vote. OR

- [You the teacher] Collect the various rules from the different groups and fashion

them into a proposal for a four rule classroom haskama. Be careful to be true to

the students’ language and intentions to the extent possible, so that the students

will recognize their work in the final product. Present the haskama to the class

and ask them to ratify it through a vote.

OPTION 2: INSIDE – OUTSIDE

- Hang up a piece of butcher paper with a large circle or oval drawn in the middle and

ample space outside the circle in which to write. Tell students that they are going to

work together to create a haskama that lists which behaviors are acceptable within

the class community—behaviors that allow each person to feel respected and

appreciated and which will help to promote a positive school experience for

everyone.

- Tell students that the circle represents the community. Inside the circle will be

written classroom behaviors that will promote a positive, learning community so

that people feel “in” the community. The behaviors should be worded in the positive

– as opposed to what should not be done. (A practice exercise for this can be found

in the first section of Option 1). Some examples of positive behaviors are:

- speaking one at a time

- listening to others

- weighing other people’s opinions even when they may conflict with yours

- giving constructive criticism in a positive way

- contacting students when they are out sick.

- Have students suggest behaviors and as they do so, list them inside the circle. One

should not worry too much about repetition, as the board can be returned to later to

remove ones that are too similar to others. Alternatively, students can write their

ideas on sticky notes and post them in the centre of the circle. Give students time to

read what others wrote, and if they have something to add, they are permitted to do

so. Further, if a student feels two or more sticky notes are similar, he or she may

move them together so that they overlap.

- Next, tell students that destructive behaviors can make a person feel outside the

community. Therefore, the class will now consider destructive behaviors and write

them on the outside of the circle. Some examples of destructive behaviors are:

- eye rolling

- interrupting someone when they are speaking

- laughing at someone’s answer

- making negative or hurtful comments about another

- making sarcastic comments

- On the top of the chart, write: We, the members of class 8A, agree to do the actions on

the inside and refrain from doing behaviors on the outside. Have students ratify the

haskama through a vote.

BOTH OPTIONS:

- The final step is to decide as a class what the process is when one observes someone

breaking the haskama and what the consequences will be. A minor consequence

might be an apology. A more serious offense might lead to peer mediation (if this

exists in the school—see Area IV of the Certification Process), adult intervention, or

loss of privilege. Tell students that when they break the haskama, they are

distancing themselves from the community.

- Be sure to hang the haskama prominently in the class. Refer to it regularly pointing

out both misbehaviors that may occur and times when students are doing behaviors

that reinforce community. Revisit the haskama a few times during the year to

reflect on it and to revise if necessary..

Wrapping Up

- Tell students that a strong community is one filled with shalom, peace. This is a

good time to introduce students to the Rodef Shalom Advisory Program which will

promote the values of pursuing peace throughout the year. The classroom haskama

is a proactive measure to promote ‘shalom bayit’, peace in their classroom ‘home’.

- You might choose to conclude with an excerpt from R. Nachman’s prayer for peace,

found on the next page.

משיר שלום, תפילה של ר’ נחמן מברסלב

עזרנו והושיענו כולנו

שניזכה תמיד לאחוז במידת השלום

ויהיה שלום גדול באמת

בין כל אדם לחברו.

ויהיה כל אדם אוהב שלום ורודף שלום.

ונזכה לקיים באמת מצוות ואהבת לרעך כמוך בכל לב וגוף ונפש וממון.

From: Prayer for Peace, R. Nachman of Breslov

Help us and rescue us all,

That we should always merit to cling to the virtue of peace,

Let there be a truly great peace between every person and his or

her fellow.

Let every person be ohev shalom, a lover of peace, and rodef shalom,

a pursuer of peace.

May we merit to always fulfill the law, “love your neighbor as

yourself” with all of your heart, body, soul and possessions.

פלא יועץ קמ”ז

ראוי בכל קהל מישראל, שיעשו הסכמות, ויתקנו לגדור גדרים לאפרושי

מאסורא, ושלא להרבות בהוצאות וכדומה. הכל לפי צורך שעה.

Pele Yoetz 147

It is proper in every Jewish community to make haskamot, and to

establish fences to guard people from doing wrong, from excessive

spending, and the like—everything according to the needs of the

time.

Click here for the PDF.