- About Pardes

- Podcasts

- Topics

- Downloads

- Donate

Rabbi Peter Stein (graduate of the Pardes Advanced Scholars Program) is currently a Bible and Talmud teacher at the Rochelle Zell Jewish High School. From 2012-18 he taught at the Frankel Jewish Academy, held the position of Chair of Bible Department, created the popular Jewish Journeys course, and received the Grinspoon Award for Excellence in Jewish Education. Rabbi Stein has a BA in Urban Studies from Yale University and an MA in Talmud from the Jewish Theological Seminary.

[Editor’s note: This is the second of a two part series outlining the theory and curriculum of Jewish Journey’s. The first part gave the overview and theory of this course.]

Part 2 – Curriculum Outline

Units

The order of the first three units is very deliberate. The course begins with God, since God is a foundational notion of Jewish belief and one’s thoughts about the other topics will largely depend upon what kind of God one believes in. Chosenness comes next because it defines the relationship between God and the Jewish people. Understanding the nature and implications of that relationship will determine what, if anything, God expects of Jews. Those expectations are then explored in the third unit, Commandedness.

Unit 1 – God

The semester begins with an inquiry into the nature of God. The first two readings explore two radically different conceptions of God. Abraham Joshua Heschel describes the classic God of the Bible – an external, living, conscious being that is capable of listening to, loving and caring about human beings. By contrast, Mordecai Kaplan describes a God that is internal, a God that is the sum of the forces of goodness, truth and beauty that run through all people. Students are familiar with Heschel’s God. They may not believe in this God, but this is the concept they were all raised with. Few have ever heard of Kaplan’s God, but many students find the concept very compelling. Further, setting up the dichotomy of an external vs. an internal God gives the students an important conceptual framework and useful language for beginning to articulate their own ideas about God.

After considering the nature of the God they believe in, students read a piece by Dr. Judith Plaskow that explores the language we use to refer to God and how that language can reflect both our conceptions of God as well as the larger values of our society. Her feminist critique of gendered God language challenges students to think first about the gendered nature of the God language found in our tradition, and second about the hierarchical nature of that language. This reading is an important introduction to feminist thought for many students who have never thought deeply about these questions. I end this lesson by having the class, as a group, write an original berachah using non-gendered and non-hierarchical language as a way for the students to experience what Jewish texts and prayer could look like through the lens of Plaskow’s critique. While some students start the exercise feeling awkward or uncomfortable with this challenge, they usually find the outcome to be very satisfying and enlightening.

Finally, the unit wraps up by examining how God can allow evil to exist in the world. This question looms large in many students’ minds, so it is important to address it. Students read a piece by Emil Fackenheim in which he teaches that God allows evil to exist so that people can have free will.

Unit 2 – Chosenness

Students begin the unit reading an article by Jill Jacobs that gives historical background about the development of the Jewish idea of chosenness. This piece is not one of the formal thinkers they will be assessed on, but is used as an introduction to the topic.

The first thinker for the unit is Deborah Waxman, currently the head of the Reconstructionist Movement. Waxman objects to the entire notion of chosenness as a dangerous idea incompatible with democratic western values. As a follower of Mordecai Kaplan, her thinking is an important example of the implications of Kaplan’s conception of God from the previous unit: if there is no external God, there is no one to do the choosing.

The second thinker is Irving “Yitz” Greenberg. He defends the idea of chosenness, but with a twist: he believes that more than one people could be chosen. Chosenness for him does not mean that Jews are better than others, but that we have a role to play in redeeming the world.

Unit 3 – Commandedness

Unit 3 begins with a traditional view of commandedness as articulated by Hayim Halevy Donin. I have used this piece sometimes as an introduction to the unit and sometimes as one of the official thinkers of the unit.

The second thinker is Gunther Plaut. This article is his introduction the book Gates of Mitzvah, a collection of writings by Reform rabbis about different mitzvot. In this piece, he says that while exactly which mitzvot one practices may differ from person to person, mitzvot are essential to authentic Jewish living. He also enumerates the process by which any Jew should arrive at their Jewish practice: first, studying what the tradition has to say about a mitzvah (Torah study), then making informed decisions about one’s practice. Most students are surprised to see that a Reform rabbi believes that deep Torah study is an essential part of Reform Jewish practice. Most students think that Reform simply equals less. This piece can be an important opportunity to begin breaking down those preconceptions about the denominations.

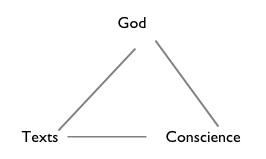

The final thinker for the unit is Jane Kanarek, a rabbi and professor of rabbinics at Hebrew College in Boston. In her piece, she shares the tension she feels between her allegiance to following halachah and those halachot that offend her moral sensibilities. She concludes that her notion of commandedness requires not blind allegiance, but rather shaping the law to fit her moral vision. One big take-away I tease out of this piece for the students is the following triangle of Jewish authority:

Ideally, all three sources of authority should be in balance and agreement. The question Kanarek deals with is what happens when they don’t? What happens when what the texts say are in conflict with one’s conscience? Which one represents God’s will? Either the texts are correct and we need to reconsider our own thinking. Or, our conscience is correct and we need to reconsider what the texts mean. I present this framework as a way of thinking about modern issues that many Jews wrestle with, especially Jewish approaches to gender and sexuality.

Unit 4 – Prayer

Prayer is, in some ways, the most challenging unit for students because so few students have had positive prayer experiences. Also, they assume that prayer means sitting in minyan reciting traditional Hebrew words out of a siddur. In this unit, I try to expand their ideas about what prayer can look like.

During the introductory lesson for the unit, I show videos of spontaneous prayer from several Christian settings and we discuss how this type of prayer experience differs from the type of fixed prayer students are used to from the Jewish world. We then experiment with spontaneous prayer by sitting in a circle for 10 minutes in complete silence except for when someone is moved to offer up a spontaneous prayer from their heart in English. This experiment is based on the spontaneous model of prayer practiced by Quakers. Students have found this exercise to be very meaningful and appreciated having their comfort zone stretched in a new direction.

This theme is further developed in a Jewish context with the unit’s first thinker Zalman Schachter-Shalomi, the late rebbe of the Jewish Renewal Movement. In this piece, Reb Zalman gives his prescription for how to create a meaningful prayer experience. The prayer experience he describes is an individual, spontaneous experience where one attempts to connect directly with God, not in the context of a synagogue and not through the use of the siddur. Students often find this surprising, as it does not reflect any Jewish prayer experience they have ever had, but speaks to their preference for individual meaningful prayer that comes from their own hearts.

The final thinker, Jonathan Sacks, addresses the question of whether and how prayer is effective. His assertion that God always answers our prayers, it’s just that sometimes the answer is “no”, is often a very thought-provoking idea for students.

In addition to these thinkers, I sometimes include in this unit an additional article for enrichment by Laura Geller, a prominent Reform rabbi in Los Angeles. If the Judith Plaskow reading in unit 1 looks at the language of prayer and texts, this piece uses a feminist lens to look at the content of prayer. Due to the sensitive nature of what she writes, this lesson requires a particularly mature group of students. For this reason, I have not done it with every class, but those that I have shared it with have found it to be very meaningful and, for many of the girls in the class, empowering.

Unit 5 – Israel

This unit is intended to be a discussion about the (religious) nature of the modern State of Israel. It is not a unit about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Over the years, I have tried a number of different components in this unit.

The two thinkers I have focused on are A. D. Gordon and David Hartman. Gordon provides a pre-state labor Zionist vision of Israel focused on the need for Jewish labor. It is a quirky piece that students have enjoyed. The Hartman reading provides a religious Zionist view of Israel as a living laboratory for implementing Halachah in a functioning, morally complex society. Around this core, we have looked at the founders’ view of the state as described in the Declaration of the Establishment of the State of Israel, a Holocaust survivor’s view from Ari Shavit’s My Promised Land, and have explored contemporary issues such as running buses on Shabbat and the Chief Rabbinate’s monopoly on marriage and divorce that speak to different views of what the state should be.

Mini-Units

In addition to the five main units, there are a number of other topics that I include in the course to further enrich students’ exploration of their beliefs. How many topics depends on the amount of time available during the semester.

Holidays

During the fall holidays, I have dedicated several days prior to Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur to doing serious introspection and teshuva in light of the things being discussed in the course.

What does it mean to be religious?

Students often times use the word religious to mean Orthodox. In this mini-unit, we explore a number of different models of what it might mean to be “religious”. The goal is to help students take ownership of this word and to more seriously consider the possibility that they might be a religious Jew.

Denominations

Students come into the class thinking Orthodox means you do the most, Conserve means you do less and Reform means you do very little. The goal of this unit is to break down these misconceptions and help students understand what the different denominations actually stand for. In the past, I have had students research the denominations in class and make presentations about them, while I have filled in important information they may have missed. It might be a very worthwhile idea for the future to bring in community rabbis from the different denominations to make the case for their denominations.

Homosexuality

Each semester, I lead a two-day discussion about homosexuality and Judaism. This originally started at the request of students. The discussion begins with familiar texts from the Torah and different Jewish legal codes that seem to prohibit homosexual behavior among Jews. This is the view students are familiar with. My goal is to help students see that there are other ways to understand these texts that lead to different conclusions. I use this issue as an example of a dilemma in the triangle of Jewish authority mentioned above where what the texts seem to say comes in conflict with many people’s conscience on this topic. I bring a range of contemporary responses to this issue, including Orthodox thinkers who seem to (just about) sanction same-sex relationships. I also share my own thinking on the subject, showing how I can have loyalty to the traditional texts while also believing they are not referring to today’s gay and lesbian couples. My thinking on this topic is heavily influenced by Rabbi Steven Greenberg’s book Wrestling With God and Men, an invaluable resource on this topic. If one is going to address this topic, I believe it is important to show a path how Judaism can be reconciled with homosexual relationships. Presenting the historical view that these relationships are forbidden and leaving it at that can do great damage to our students.

Open Forums

Once or twice during the semester, if there is a free day, we will have an open forum to discuss some topic of interest to the students that is not already in the curriculum. I will usually solicit ideas from the students in advance and prepare a few sources on the topic to help frame the discussion. We will then spend the period discussing our thoughts and questions on the topic.