- About Pardes

- Podcasts

- Topics

- Downloads

- Donate

Often, when we teach about Jewish holidays, a major (and necessary!) element of focus is meaning-making. In other words: what do the “big ideas” of this holiday say to us? How might the themes of the holiday and the values they evoke be relevant to our lives today?

So on Pesach, for example, we might highlight the idea of slavery vs. freedom, and ask ourselves how we might ensure true physical, psychological, religious or spiritual freedom for all in 2018. On Sukkot we might hone in on the themes of mindfulness and graciousness, as we acknowledge that what we have in this life is not solely a result of our own hard work, but a gift from God.

But what happens when what a holiday is all about – its underlying themes and motifs – is not particularly clear? When what we think of the holiday doesn’t exactly jive with our earliest sources on it? How do you figure out how to make meaning out of it then?

Take Tu B’Shvat, for instance. Is that a holiday with a clear unequivocal message, such that we can easily make meaning from it with our students?

Well, for sure, you might say. Of course Tu B’Shvat is a holiday with a clear unequivocal message. We all know it’s a reminder to take care of the environment, wherever one lives, because if we don’t then we will end up in a very unhealthy, messed up world. So plant trees! Don’t cut them down! Reduce! Reuse! Recycle!

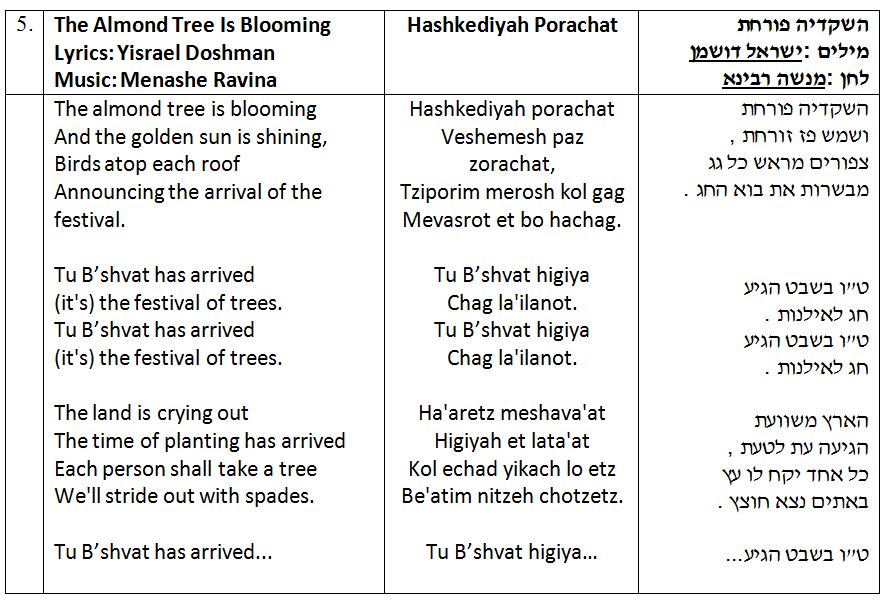

But wait – isn’t it really about a strong, positive, palpable, physical, fruity connection to the Land of Israel and not actually about caring for the environment? Otherwise, why is HaShkedia Porachat the Tu B’Shvat anthem? And if so, where did that whole environmental bent come from??

But wait yet again! Aren’t the tree fruits we eat on Tu B’Shvat really just symbolic, and not physical at all? In fact, don’t some people tout a metaphysical message connected to this day?

And wait just one more time – because if you look at the original mention of this holiday in our traditional sources, you won’t find any of these messages at all!

Oh no!

As such:

Can we authentically give our students a more modern meaning-making message about environmentalism, love of the Land of Israel, or a connection to the Divine, when it seems that the holiday isn’t about those things at all – when one goes back to the original source? And if we do talk about those themes that feel more relevant to our students’ lives today, are we corrupting its true significance? Are we doing ourselves and the holiday some sort of disservice?

It is my sense that not only is it okay to teach about the environment in connection with Tu B’Shvat, if that is meaningful to you and your students, but it is also completely authentic. I believe this to be true because since its first appearance some 2,000 years ago, Tu B’Shvat has grown and changed and evolved, and along with it its themes and big ideas have developed and changed as well. It is almost as if the holiday has shed its skin more than once over two millennia, or undergone a series of facelifts.

In Hebrew/Jewish, the way to say “reincarnation” – when the soul or spirit, after the death of the body, comes back to life in a newborn body – is גלגול נשמות. Like the word for wheel, גלגל, גלגול means the act of spinning or rotating. In biology, גלגול means metamorphosis or transformation. Essentially, a soul that moves from one bodily incarnation to another is evolving, changing, transforming itself from one thing to another.

Holidays are no different. They too grow and change over time. Along the way, they take on different themes or big ideas, depending on what is going on in the world at that moment and what the celebrators of that time period need.

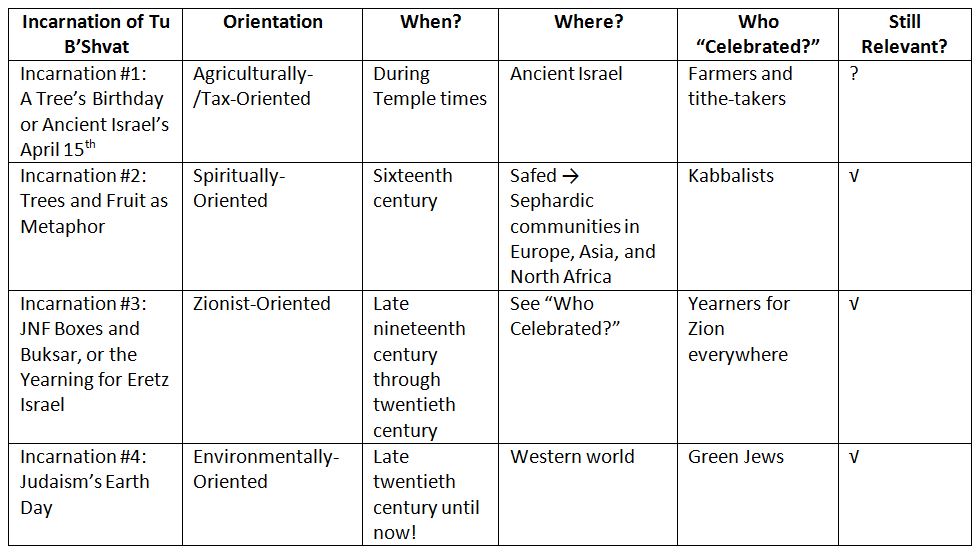

Tu B’Shvat is an excellent example of this גלגול phenomenon. One can see, when analyzing the relevant primary sources, that over the past two thousand years Tu B’Shvat has shed its skin, had facelifts, or reincarnated itself, at least three times.

Gilgul #1: A Tree’s Birthday or Ancient Israel’s April 15th

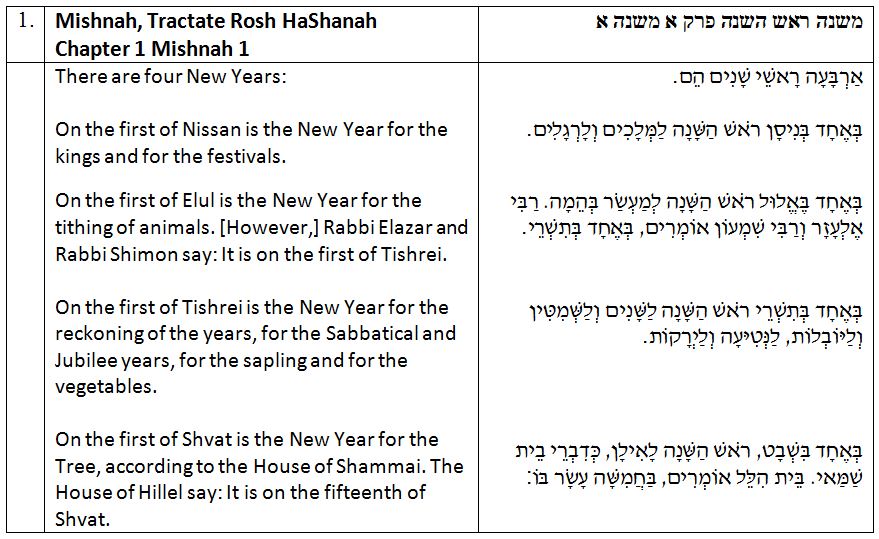

Our first introduction to Tu B’Shvat is in the Mishnah, Tractate Rosh HaShana, in a discussion about what constitutes the “new year” in the Jewish calendar:

We understand from this mishnah that, according to Hillel, the fifteenth day of the month of Shvat is considered the “New Year for the Tree.” Shammai votes for the first day of Shvat, but like in almost all cases, Hillel’s opinion overrides that of Shammai.

We do not yet technically see the language of “Tu B’Shvat” in this mishnah, but we can intuit that Tu (טו) is actually tet-vav (ט”ו), the Hebrew alphabetical version of 15 (if ט/tet=9 and ו/vav=6, then ט/tet+ו/vav=15). So Tu B’Shvat literally refers to Hillel’s choice of date for the “New Year for the Tree.”

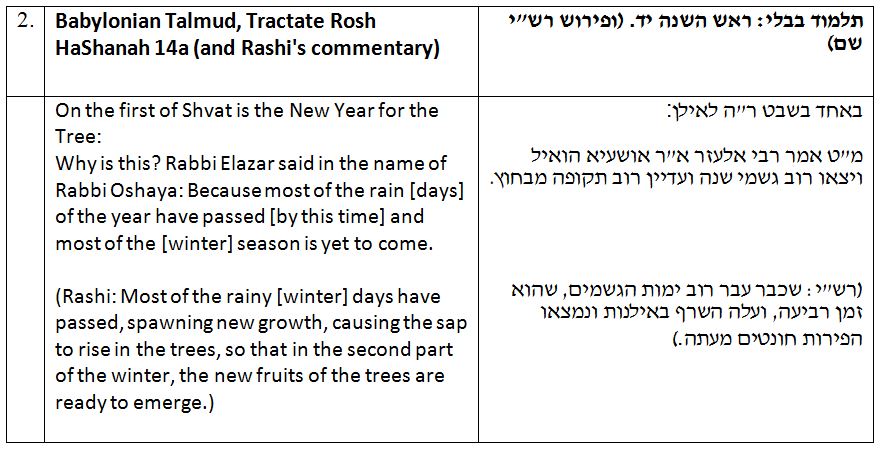

We turn to the gemara on this mishnah (and Rashi’s commentary on the gemara) to try and discern why this date was significant and chosen as the “New Year for the Tree”:

From the mishnaic source we can ascertain that the original Rosh HaShana for trees – the original Tu B’Shvat – was not a holiday, per se, where something was celebrated or commemorated, but rather a technical cutoff day for tax purposes. Each of the four New Years was, in some capacity, a technical cutoff date. If something happened before that date, it belonged to the previous year. If it happened after that date, it belonged to the new year.

Taxes at the time the mishnah is referring to were not about filling in FBARs or W4 forms, clearly; most people were subsistence level farmers, and taxes were paid, in the form of the produce they raised, to the Temple, in various combinations of tithes.

Tu B’Shvat was the technical cut off day for tree taxes. If your trees blossomed and bore fruit before the fifteenth of Shvat, then you started giving your tithes on those trees on that day. For trees that blossomed and bore fruit after Tu B’Shvat, one waited for the next Tu B’Shvat to give tithes. One might say that this date was both the end and the beginning of the tree farming cycle – that the fiscal year lasted from Tu B’Shvat to Tu B’Shvat.

Another technical halachic usage for this date concerns the commandments of orlah and neta revaii – wherein fruit from a tree in its first three years after planting is not used, as it is considered “uncircumcised,” and in its fourth year must be taken to Jerusalem and eaten there while one is ritually pure. A year, in these cases, is counted from Tu B’Shvat. If a tree is planted before Tu B’Shvat, it is considered one year old on that day, even if it is not actually 365 days old. This is the origin of Tu B’Shvat as the trees’ birthday, and is similar to the traditional way of looking at birthdays in Chinese culture.

Honestly, though – the concept of a birthday for trees, or even a Rosh HaShana for trees, is a bit misleading. Tu B’Shvat in its earliest incarnation was not a birthday to give gifts or an anniversary for appreciating trees, necessarily, but rather a marker for taxes. Calling it “Ancient Israel’s April 15th” is also somewhat inaccurate. Our farming ancestors did not have to pay taxes BY this date, as we do on April 15th; rather they could START paying taxes on that date. But describing Tu B’Shvat in these ways gives you an idea of the day’s original purpose.

Making meaning for this non-holiday holiday with your students – for this tax day – might not be the easiest of tasks. I mean, who likes taxes?! And in fact, you are not alone in finding meaning-making for this incarnation of Tu B’Shvat difficult. Because after the Temple in Jerusalem was destroyed in 70 CE by the Roman army, there wasn’t much meaning left in the day either. With no land, and no trees, no tithes were given. With no Temple, there was nowhere to give the tithes either.

It is true that during the time of the ge’onim, piutim were penned in its memory, and the Jews of Ashkenaz would omit tachanun on the date itself. But these were simply acts in memorium of a now defunct day. For 1,500 years, Tu B’Shvat had no real meaning.

Gilgul #2: Trees and Fruit as Metaphysical Metaphor

Some fifteen centuries after the Temple’s destruction, something interesting happened. Tu B’Shvat, which had lain dormant for so long like a tree in winter, began to awaken. The sap began to rise, buds began to form, and its fruit began to ripen…

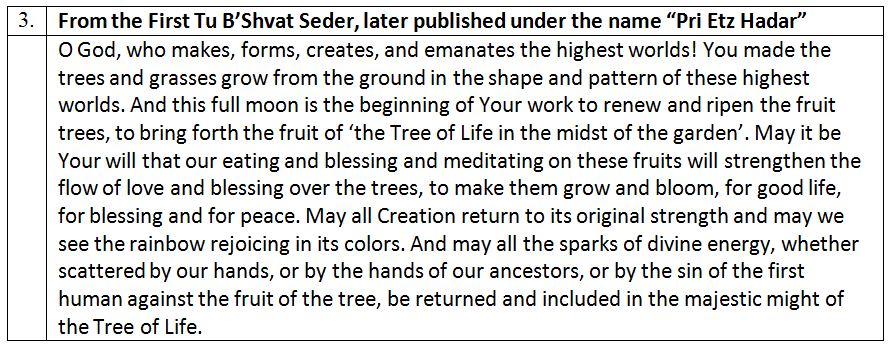

The kabbalists in sixteenth-century Safed reclaimed the day. They reclaimed its soul, and placed it in a new body – one that was spiritual, metaphorical, metaphysical. They felt perfectly comfortable doing this because, for them, the concept of the “Tree of Life” – kabbalistic code for the path to God – was such a central tenet. And here’s why:

A tree has four parts: the roots, trunk, branches, and leaves. And in Kabbalah, there are four worlds, or four planes of existence, which link our world with the Ein Sof, the infinite, nature of God: the worlds of asiyah/action, yetzirah/formation, beriah/creation, and atzilut/emanation.

So for the kabbalists, celebrating a day of trees was actually a way to celebrate their whole belief system of trying to attain closeness to God, trying to attain spiritual perfection, trying to restore cosmic blessing by strengthening and repairing the “Tree of Life.”

Along these lines, kabbalists like Rabbi Isaac Luria created a seder – like on Pesach, or Rosh HaShana. In this seder, 30 fruits would be blessed and eaten (ten each for the three lower worlds), and four cups of wine would be drunk in a precise order, in order to bring human beings, and the world, to a more spiritually transcendent state. In the words of Rabbi Chaim Vital, Luria’s student, the goal of the seder was “to influence the abundance of the holy tree – the Tree of Life” (“להשפיע את שפע האילן הקדוש – עץ החיים”).

This practice spread among Sephardic Jews in Europe, Asia, and North Africa, and was Tu B’Shvat for the next several hundred years.

Despite the complex nature of this metaphysical approach to trees, applying it to our lives today is not so difficult, because the idea of similes/metaphors/synectics is something our students are familiar with. You might give them the sentence stem: “A tree is like a path to God in that…” and let them fill in the rest with their own original explanations. Or you might ask them to create mixed media collages of trees that ALSO represent the idea of working towards a more perfect world.

You might also extend the tree/spirituality metaphor and look at varied types of fruit as metaphors for spiritual qualities to which we aspire. The Jewish bookshelf has lots of sources about how different fruits represent different qualities. Dates represent righteousness and unyielding strength, as in צדיק כתמר יפרח; in the Talmud, pomegranates represent being full of good deeds; almonds represent enthusiasm to serve God, and more.

One classroom activity might find you sharing with students what qualities each of the fruits represent, then challenging them to figure out WHY each fruit represents that quality (based on the way the tree or fruit looks, tastes, develops, etc.). Then you might even have students consider which quality they would like to try on in their own lives, then reflect on that in journal form.

Gilgul #3: JNF Boxes and Buksar, or the Yearning for Eretz Israel

Three Hundred Years Later…

While the kabbalists’ sixteenth-century take on Tu B’Shvat was a spiritual one, at the end of the 1800s, Jews started actually returning to the land and placing value on physically planting trees and building up agricultural practices. A tree was no longer a metaphorical, metaphysical tree of life; it was an actual tree that could be planted and harvested and looked at in pride.

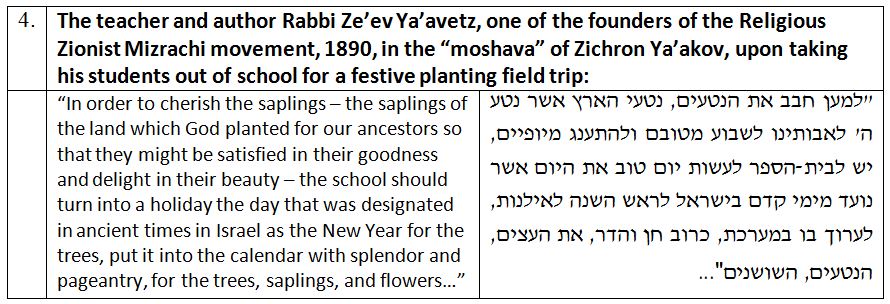

On Tu B’Shvat, 1890, one of the founders of the Mizrachi Religious Zionist movement, Rabbi Ze’ev Ya’avetz, took his students out of the classroom to plant trees in Zichron Yaakov, at that time an agricultural colony.

This custom of tree planting with one’s students on Tu B’Shvat was adopted 18 years later by the Jewish Teachers Union, and some time after by the Jewish National Fund as well.

By the early twentieth century, Tu B’Shvat was synonymous in Eretz Israel with a physical and agricultural revival – the beginnings a renaissance of the Jewish people in their own land. The almond tree –the shaked – one of the earliest budding trees of the winter season, symbolized renewal and regrowth of all types.

In this vein, many of Israel’s important institutions chose Tu B’Shvat as a day for laying their cornerstones. Hebrew University was inaugurated on Tu B’Shvat 1918, the Technion of Haifa on Tu B’Shvat 1925, and the Knesset on Tu B’Shvat 1949.

For the few Jews living in Eretz Israel at the time, this new incarnation of Tu B’Shvat was clearly relevant and significant – representing their tireless work to build up the land. But what about the people who lived outside the land? Was this a meaningless holiday for them? Or could it hold some meaning for them too?

Of course it could. Tu B’Shvat was treated as a tangible focus for their yearning to return to the Land of Israel. They put money in their JNF pushkas, they ate buksar (carob – the only fruit they could get from Israel at that time that wouldn’t spoil), and dreamed of having the chance of visiting Eretz Israel one day.For our students, a discussion of their varied connections to/feelings about Israel can be kicked off on Tu B’Shvat.

Gilgul #4: Judaism’s Earth Day

For seventy years now, not only have Jews been able to visit the State of Israel, they’ve been able to choose it as their home, if they wanted to. And for 30-odd years, the focus in Israel has been less about survival, and more about living a normative life in a normal Western country.

So what is the latest reincarnation of Tu B’Shvat? As the Western world has become increasingly, and necessarily, concerned with the environment, many Jews have turned Tu B’Shvat into a day to highlight the need for preserving the environment. People have created Tu B’Shvat seders and initiatives that focus on the environment – essentially, Judaism’s Earth Day.

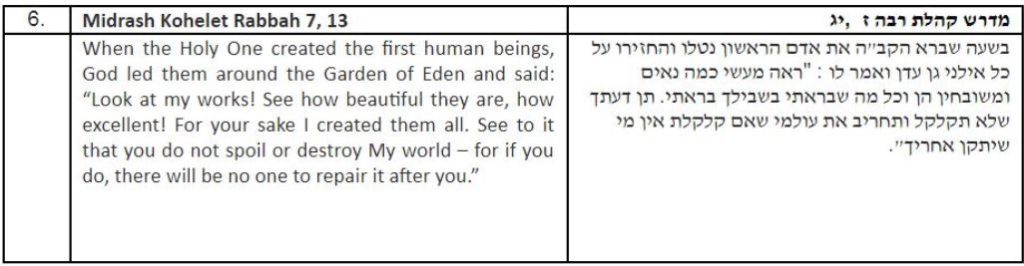

It is important to note that while this gilgul feels modern and of crucial significance in our day and age – meaning-making is pretty clear in this case – it actually echoes an ancient Jewish value. It seems that at its heart, Judaism is an environmentally-friendly religion.

Conclusion

As we said earlier, holidays by necessity grow and change over time. Along the way, they take on different themes or big ideas, depending on what is going on in the world at that moment and what the celebrators of that time period need. Tu B’Shvat is just one example of this phenomenon. What’s nice about 2018 – is that we can take pieces of all three, if not four, of the gilgulim, and create a Tu B’Shvat that has a variety of layers of meaning. And beyond, I for one am very interested to imagine what the next gilgul of Tu B’Shvat might be…..